300 Jarvis Street, Toronto | originally Frontenac Arms (1931)

- Peter J. Marshall

- Sep 7, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Jun 24, 2025

When Mary Ingram purchased the William Adams house on Jarvis Street north of Gerrard in November 1928 she planned to replace it with an apartment building like the one she was currently constructing nearby[1]. However, the Great Depression had other plans. In January 1930 the mortgage was foreclosed and the lot sold off, setting a pattern that would be repeated time and again with owners of this property.

Frontenac Arms Apartment Hotel (1931-1964)

Undeterred by the ongoing economic crisis, Syrian born developer Peter Khoury bought the property and in June he began construction of a ten-storey apartment building that would be the tallest of its kind in the city. Designed by architect J. A. Thatcher and built at a cost of $400,000, the Frontenac Arms opened in July 1931 boasting an elaborate rooftop garden, underground parking, two “fast type” elevators, switchboard service and a bell boy. Of the 117 units at 306 Jarvis (the building's original address), seventy-five percent were bachelor apartments euphemistically described in advertisements as "two roomed suites". Perched atop the east wing of the edifice was a two-bedroom penthouse with spacious rooftop terraces to the north and south.

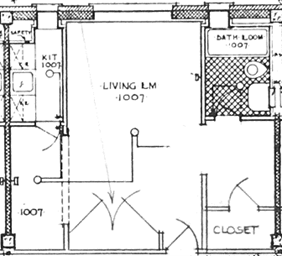

LEFT: Illustration of the original building (The Journal, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, August 1931). CENTRE: Original blueprints showing a typical "two roomed suite" with a double-door bed closet to store a roller bed (Toronto Archives). RIGHT: An example of the type of roller bed that was purchased for every apartment in 1933 (via National Association of Home Builders).

Unfortunately, the stylish amenities failed to attract tenants during the economic slump and within a month the building was rebranded as an “apartment hotel” offering furnished and unfurnished units to temporary and permanent guests. This revised business model required further investment to outfit the dedicated hotel suites, construct a reception lobby and small dining room on the first floor and pay the requisite staff. Despite briefly teetering on the verge of bankruptcy the conversion was completed in late 1933 and proved successful enough to keep the Frontenac Arms in business through the remainder of the Depression and onward through World War Two. However, the transient clientele and increasingly seedy neighbourhood earned it a reputation that was a far cry from the lofty vision of the original builder.

Promotional photos from 1947 include the small dining room and lounge on the first floor facing Jarvis Street where two one-bedroom apartments had originally been planned (Canadian Architectural Archives). Some of these photos were used in a promotional postcard seen at the lower right (author's collection).

W. Harold Allen next bought the building in 1952 for $700,000 and it was business as usual for his first few years. Then in 1957 he leased the property to a management company bankrolled largely by American investors with an ambitious vision to transform it into a proper hotel.

The first phase of the “New" Frontenac Arms Hotel premiered in January 1958 with an emphasis on the lucrative weddings, banquets and meetings trade. The building had been completely renovated to provide five large dining and banquet rooms, a bar and a 24-hour coffee shop. This necessitated a takeover of the first floor and basement garage (previously accessed by a laneway off Mutual Street) and so the house south of the hotel was purchased and demolished to make way for an aboveground parking lot. Guest capacity was also increased by by repurposing the kitchen and dining spaces of the original apartments to create dozens of new rooms. Judging by the almost immediate appearance of Frontenac Arms wedding reception announcements in newspaper social columns, the plan worked.

The crowning touch came on April 1959 with the debut of the Frontenac Room supper club. Despite the structural limitations of a 30-year-old building – support pillars blocking audience views and a low ceiling forcing servers to bob in and out of spotlight beams – critics were won over by the quality of the musical and comedy acts that appeared each week. The following year saw the arrival of the Chelsea Club offering after-hour jazz, beat poets and hot coffee to Toronto’s original hipsters.

1958 promotional photos featuring the new surface parking lot, new dining and banquet rooms and renovated guest rooms (Toronto Archives). In the bottom right is a 1959 ad promoting dining, dancing and live entertainment three times nightly at the new Frontenac Room supper club.

The hotel’s management even encouraged their neighbours to join in the revitalization of the neighbourhood. Jarvis Street businessmen, landlords and institution representatives were invited to a “Lift the Face of Jarvis” meeting at the hotel in March 1959 where the Frontenac Arms provided free paint in exchange for a commitment to beautify their own buildings.

From all outward appearances, the $625,000 hotel transformation was a great success. But behind the scenes J. K. Kinsella, a Canadian partner in the management company, realized in July that there would be no further funding from his U.S. colleagues. Kinsella called together the firm’s creditors and convinced most to give him more time in exchange for contributing $50,000 of his own money and instituting a star entertainment policy to draw more business. Then just as the strategy was beginning to pay off, the hotel owners forced the firm into receivership for overdue rent. On December 22 the company declared bankruptcy leaving sixty five employees with $7,500 in unpaid wages only three days before Christmas. Gallant to the end, Kinsella paid the outstanding sum himself.

Following the demise of the management company, Allen’s estate assumed control of the hotel and scaled back costs by replacing the star headliners with a more modest dinner and dancing format at the renamed Club Frontenac. The business reverted to also renting rooms on a long-term basis. This low-key approach continued until September 1964 when Allen’s widow sold the property to entrepreneur David Coplan for just over a million dollars marking the start of a new chapter, albeit one which would play out much the same as the old.

LEFT: 1960 ad for scaled-back dinner entertainment. CENTRE: 1960 ad for the Chelsea Club. RIGHT: The hotel in 1964, its last year as the Frontenac Arms (Canadian Architectural Archives).

Carriage House Hotel (1965-1979)

Sixty-one-year-old David Coplan was involved in several profitable business ventures at the time of his purchase of the Frontenac Arms, most notably the lavish French restaurant Les Cavaliers at nearby Church and Granby streets. His vision for his new acquisition was to restore its role as a dedicated hotel and imprint it with his own luxurious style.

Coplan moved quickly. Just months after taking ownership, December newspaper ads were proudly announcing the debut of The Carriage House Hotel and promising that the ongoing extensive upgrades would all be done “in the very grandish and opulent manner”. The transformation was evident as soon as guests arrived. A large, canopied entrance was added to the building’s south face providing direct access from the parking lot which now offered valet service. The lot itself was extended to Mutual Street, lined with gas lights imported from England, and christened as “Carriage Lane” in hotel advertising. Once inside the hotel, guests could imbibe at the Lamplighter Lounge, chow down at the Cattlemen’s Steakhouse and Oyster Bar or dine in booths decorated like Polynesian huts at The South Pacific restaurant. On the floors above, suites were remodelled with decorator designs and furnishings.

FIRST FOUR IMAGES: promotional photos from 1965 and 1967 showing the new South Pacific Room and possibly the Lamplighter Lounge (digitally colourized) as well as the new side entrance off the spruced up parking lot (Canadian Architectural Archives). BOTTOM CENTRE: 1965 newspaper advertisement. BOTTOM RIGHT: postcard of the slightly renamed Carriage House Motor Hotel.

Sadly, the ambitious makeover suffered the same fate as its 1958 predecessor. In December 1965, just one year after the relaunch, Coplan’s mortgage holder forced him into receivership. Although the property was put up for sale in 1966 the mortgagers eventually decided to operate the hotel themselves. In January 1968 they announced that the business was under their new ownership with new furnishings and a somewhat new name: Carriage House Motor Hotel. For the next four years it appears that the owners managed to avoid reverting to long-term rentals, although at one point they did assist the city’s Welfare Department by temporarily lodging families left homeless due to a chronic shortage of short-term housing at the time.

The property next changed hands in 1972 when it was acquired by a development consortium led by realtor John Franciotti. The new owners restored the previous Carriage House name (sans "motor") and modernized the branding with a hipper logo and new signage. They closed the themed restaurants and opened The Jean Factory, a downstairs bar The Globe and Mail described as “a student hangout where the clientele orders its draft by the tray load and likes its music loud, fast and simple”.

The scaled back operation continued to lose money, though, and Franciotti was open to new ideas. When the venue’s gay manager suggested they try catering to his community Franciotti went all in, launching Toronto’s first gay hotel in September 1973, just one year after the city’s premier gay pride march. Visitors from Detroit and New York booked blocks of rooms for their Toronto vacations while local men and (initially) women danced to jukebox disco in the two spacious downstairs beer rooms or socialized upstairs in the lounge. The venue proved to be such a welcoming alternative to the city’s few other gay hangouts that before long it was impossible to get into the place any later than eight o’clock. The novel addition of a Sunday afternoon buffet a few months later also became an instant hit and no doubt made for a diverse mix of people in the hotel parking lot shared with the Jarvis Street Baptist Church every Sabbath.

TOP LEFT AND CENTRE: New branding and a new bar for The Carriage House circa 1975 (Toronto Archives). TOP RIGHT: 1974 contest to select "Mr. Club" sponsored by The Club gay bathhouse on neighbouring Mutual Street (Body Politic volume 11). BOTTOM LEFT: 1973 ad for the hotel in a national gay newspaper (Body Politic volume 10). BOTTOM CENTRE: review of the hotel's bars and accommodations in 1974 newsletter from University of Waterloo's gay liberation movement (ArQuives). BOTTOM RIGHT: Groovy 1970s wallpaper uncovered in the basement during 2023 renovations and confirmed by a former patron to be the original décor from the gay bar (Peter Marshall).

One thing that would have united churchgoers and nightclubbers alike was a leeriness about the neighbourhood’s ongoing decline. This trend is evident in period newspaper reports of three hotel employees being bound, gagged & robbed in 1972, a waiter being stabbed by a customer as he tried to stop him from prying apart a jukebox in 1975, and a man being severely slashed with a razor by muggers in the parking lot 1979. (In the latter incident a hotel waiter saved the victim’s life by reviving him with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.)

The former church-owned parking lot was just one of several adjacent properties that the consortium acquired in anticipation of a large-scale redevelopment of the area. The first plans submitted to the city in January 1973 were for a 600-room apartment hotel that would be constructed next to the existing building. Presumably the permit requested was denied because the owners were back in front of city council in 1976 with even grander plans for “Carriage Court”, a project comprised of a senior’s residence in the converted hotel along with a twenty-three-storey apartment building and townhouse complex. That proposal was also quashed when the city restricted new construction to rein in rampant growth downtown and the corresponding demolition of older buildings. Undeterred, the owners spent the next two years appealing the decision at City Hall and the Ontario Municipal Board until they finally received approval for a modified version of the plan. Ownership was transferred to a new partnership and work began on yet another hotel renovation under yet another business name.

Essex Park Hotel (1979-1998)

At the same time as he was pursuing the Carriage Court development, Franciotti had his sights set on a much grander goal: the purchase and restoration of the King Edward Hotel. Lacking the financial means to acquire such an expensive property he turned to his Carriage House partner Emilio Valentini, to form a new real estate company called Trans-Nation. In addition to bidding on the King Eddy, the firm took over ownership of the former consortium’s Jarvis lands and in early 1979 was renovating the renamed Essex Park Hotel (the conversion to a senior’s residence having proven impractical) while simultaneously constructing the neighbouring Essex Place townhouses.

This latest renovation cost $2.5 million and was completed in October 1979. Promoted as “a first-class hotel for businesspeople” it featured air-conditioned guest rooms, a new restaurant called E. J.’s Lounge, a new address - 300 Jarvis - and new management under the Quality Inn banner.

TOP LEFT: 1979 renovations included replacing the original first floor windows on the south elevation with bay windows for the restaurant and covering the adjacent brick (Toronto Archives). TOP CENTRE: The front entrance was no longer used so was converted into a window (Toronto Archives). TOP RIGHT: the faux stone block facing on the ground level in 1988 (Archives of Ontario). BOTTOM LEFT AND CENTRE: Matchbox with the original Essex Park branding (Bunny Sicard). BOTTOM RIGHT: The streamlined Essex Park logo introduced as part of the1990 renovations when the front entrance was re-opened and remodeled (Peter Marshall).

The partnership with a multinational hospitality chain would mark the end of the building's years as a apartment-inn hybrid operated by independent proprietors but not its cycle of revolving bankruptcies. In the spring of 1987 the hotel was transferred from Trans-Nation to a holding company under power of sale and in November that year was purchased by Polygrand Developments for $8.8 million. The Hong Kong real estate company arrived on the scene with a splash in March 1988 when chairman Kenneth Lo flew in to host a Chinese New Year party at his new property attended by the Chairman of Metropolitan Toronto, the former lieutenant-governor of Ontario, and celebrated author and activist June Callwood. Polygrand officials excited the guests with talk of potential plans to develop the hotel parking lot into an office complex and day care centre but by July had decided on a different scheme: they would erect a condominium and undertake an extensive $3.5 million dollar renovation of the hotel. This would mark the fourth major overhaul in the sixty-year history of the building and coincided with its official designation as a heritage property that year.

A call for tenders was issued in December and renovations took place throughout 1989 and into 1990 while the hotel remained open for business. The alterations included reducing the guest room count from 110 to 102 partly due to the conversion of the two Jarvis-facing suites on second floor into meeting rooms and the removal of two adjacent suites to allow for a feature staircase providing access to these new facilities and a pedestrian bridge that would connect to the condominium. Below ground, the basement lounge space was converted into offices and public washrooms along with a passage to new underground parking beneath the condo. When work was completed in June 1990 the significant improvements qualified the hotel to upgrade to Quality's higher-end Clarion brand.

Meanwhile, more major changes were underway next door. As past hotel owners knew all too well, no amount of renovations to the original apartment building could eliminate the physical barriers it placed in the way of creating facilities that could compete with those of modern hotels. Polygrand’s solution to the old quandary was a novel one for the time: incorporate the larger facilities into a brand new building and share the usage and maintenance costs with the condominium. Consequently, once the Metropolitan Essex was completed in 1991 hotel guests were able to cross an enclosed pedestrian bridge to enjoy an indoor pool, health club, sauna and squash court as well as more spacious ballrooms.

Yet despite the ambitious upgrade – or possibly because of it – in 1997 Polygrand became the building’s fourth owner to declare bankruptcy and the property was back on the market in early 1998.

Ramada Hotel (1998-2020)

Just a few months after going on sale for $10.5 million, the hotel was in the hands of Espartel Investments. Following a familiar pattern, the new owners put their own stamp on the business by undertaking yet more renovations and switching up the branding, this time operating under the Ramada Hotel and Suites banner. Downstairs the restaurant was reinvented as Bistro Lounge and Restaurant while on the top floor the original penthouse apartment was converted to a meeting space named the Frontenac Room in a fitting tribute to the building's past.

TOP LEFT: The original Ramada exterior (Bob Krawczyk / TOBuilt). TOP CENTRE: Original one-bedroom suite (archived Ramada website). TOP RIGHT: During the 2006 renovations the first floor's modern facing was temporarily removed, revealing the walled-up windows of the original apartments (Peter Marshall). MIDDLE LEFT: New exterior facing and new restaurant in 2006 (Booking.com). OTHERS: refurbished Frontenac Room in guest room configuration, new Shades restaurant and bar, renovated front lobby, Parkview meeting room overlooking Jarvis Street on second floor (TripAdvisor).

In 2006 it was time for another refresh. The hotel was upgraded to the Ramada Plaza brand, the restaurant was renamed Shade and given a new executive chef, guest rooms had their outdated flowery comforters replaced with modern duvets and a 1960s one-storey addition to the north face was converted to the Solarium meeting room. Renovations and refurbishments continued periodically throughout the following years to update the hotel's look and in 2020 Espartel became became the inn's longest owners, surpassing original developer Peter Khoury's twenty-two year stint. At that time they were on the eve of the building's fifth complete overhaul when they were blindsided along with the rest of the world by the COVID pandemic. Faced with the prospect of scraping by at skeleton capacity for an indeterminate length of time, the owners made a bold choice in March to to shutter the hotel completely and dive headlong into renovations that would prepare it for an all-new chapter in its ongoing saga.

Hampton Inn and Suites (2023-present)

In theory, the plan to gut the closed hotel all at once rather than doing it piecemeal while staying open for business meant that the renovations would be completed much sooner. However, just as the Great Depression had altered the course of the building's original construction, the pandemic had its own adverse impact on Espartel's construction plans. Supply chain and labour shortages eventually slowed the work to a snail's pace and the reopening as a Hampton Inn & Suites property was postponed a number of times. Finally, three years after the project began, a new contractor was hired and the pace kicked into high gear. As of this writing, the extensive renovations are nearly complete and reservations are being accepted for November 2023.

[1] Ingram built York Manor apartments at 262 Jarvis in 1929.